Dungeon Generator Part 1

In which I start tinkering with an idea for a dungeon crawler game.

I like procedural things. I find their existence fascinating. I mean, I don't think that 'procedural' should ever be used as a bullet point or as part of your USP as it's a content production tool - it would be like saying "Features 3D models produced in Maya" or "Textures made with Photoshop" - but they're fun to learn about and even more interesting to create.

Creating an interesting dungeon is a simple enough idea. You should probably have Rooms and Corridors then fill them with Stuff. Many people do this and I shall be no different. Well, I shall be a little different in that this one isn't going to use blocks. A cursory Google search for 'procedural dungeon generation' comes back with a whole bunch of hits, almost all of which are designed to be used with a tile-based map.

I don't want to do that.

I got the idea in my head that modern dungeon crawlers are too... well, safe. Most of them come with some kind of auto-map that fills in as you go along. You always know where you've been and what you've got left to explore. Failing that, as has previously been established, most are built on a tile-based system and furthermore, those are normally aligned orthogonally. That means that you can, at least, get your bearings by remembering which direction you were heading in.

I'd like to create a dungeon that you have to actually explore. One in which you can become lost. Fail to make it back to the surface. Add some real jeopardy in there.

To that end, I shall make mine out of polygons. Lovely, randomly-oriented polygons. Corridors will go off at all kinds of angles and the camera will rotate freely, meaning it will be quite easy for people to lose their bearings. I'll need to provide plenty of landmarks or other distinguishing features for rooms otherwise that'd just be mean.

The first step is to create a simple room. My approach to this is to generate a bunch of vertices in a circle. Once that's done, I can then jiggle them outwards and inwards by a random amount to create a kind of splat shape. Well, maybe not a splat but a rugged former-circle.

That looks a bit crap, so the next stage is to smooth it out a bit. That's done by going through each vert, taking the average position of both neighbours and lerping a little towards that new position.

Finally, I do another pass to normalise vertex positions. That is, I create another set of verts that are a uniform distance apart from each other. This means they don't completely follow the path I've already described - cutting the odd corner here and there - but it looks cool and will be more useful in the long run.

Boom! Room outline done. The next step is to fill it all in.

In a previous incarnation of this approach, the interior was filled by creating segments linked to a central point. The problem with that is that you can't have concave shapes. I need something a little different. Also, although I said no grids earlier, I think a grid would be perfect for filling out the centre in a rough fashion. It might also make it easier later on if I need to do navigation and the like.

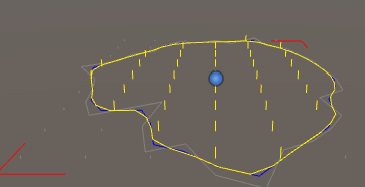

I found a formula for determining whether or not a point was inside a polygon and applied it to every point inside the room's bounding box. Check out this image:

The grey line is the rough outline - what happened to the circle after I perturbed the verts. That sounds nasty - perturbing verts. Shame really - it's going to crop up a lot.

The blue line is what happens after the smoothing with the final position being shown as a yellow outline.

The two red brackets show the extents of the room and the little vertical lines are the grid within it - grey ones are outside the polygon and yellow ones are inside.

The next step involves going around and removing any 'widowed' verts from the edges. Those are verts that, whilst being inside the polygon they don't have enough neighbours inside the polygon to form a quad. You can see an example of one sticking out at the very top of the image above. Once that's done, it's easy to go through and create the mesh for the central part of the floor - after a small amount of vertical perturbation, of course.

Rather than re-use each vert to create a single, smooth mesh, I've elected to duplicate the verts at each point so as to create a flat-shaded aesthetic. It will also enable me to mess around with individual UVs should the need arise.

Now all I needed to do was somehow join the interior floor grid with the outline. The first stage is to create a skirt - another set of verts extruded from the outline. My plan was then to take the interior ring of those and snap them to the nearest point on the outside of the grid. Quantising the position was easy but it still left me with gaps where a pair of verts might choose the same point to move to and leave grid edge verts untouched. I still don't know how to solve this so I opted for a different solution.

Simply extend the skirt even more and raise up the outside edge. Then the Z-buffering can sort everything else out instead! It gives the floor a natural, cave-like look as well as rounding off the outside edge of the grid.

I like procedural things. I find their existence fascinating. I mean, I don't think that 'procedural' should ever be used as a bullet point or as part of your USP as it's a content production tool - it would be like saying "Features 3D models produced in Maya" or "Textures made with Photoshop" - but they're fun to learn about and even more interesting to create.

Lose Yourself

Creating an interesting dungeon is a simple enough idea. You should probably have Rooms and Corridors then fill them with Stuff. Many people do this and I shall be no different. Well, I shall be a little different in that this one isn't going to use blocks. A cursory Google search for 'procedural dungeon generation' comes back with a whole bunch of hits, almost all of which are designed to be used with a tile-based map.

I don't want to do that.

I got the idea in my head that modern dungeon crawlers are too... well, safe. Most of them come with some kind of auto-map that fills in as you go along. You always know where you've been and what you've got left to explore. Failing that, as has previously been established, most are built on a tile-based system and furthermore, those are normally aligned orthogonally. That means that you can, at least, get your bearings by remembering which direction you were heading in.

I'd like to create a dungeon that you have to actually explore. One in which you can become lost. Fail to make it back to the surface. Add some real jeopardy in there.

To that end, I shall make mine out of polygons. Lovely, randomly-oriented polygons. Corridors will go off at all kinds of angles and the camera will rotate freely, meaning it will be quite easy for people to lose their bearings. I'll need to provide plenty of landmarks or other distinguishing features for rooms otherwise that'd just be mean.

A Basic Room

The first step is to create a simple room. My approach to this is to generate a bunch of vertices in a circle. Once that's done, I can then jiggle them outwards and inwards by a random amount to create a kind of splat shape. Well, maybe not a splat but a rugged former-circle.

That looks a bit crap, so the next stage is to smooth it out a bit. That's done by going through each vert, taking the average position of both neighbours and lerping a little towards that new position.

Finally, I do another pass to normalise vertex positions. That is, I create another set of verts that are a uniform distance apart from each other. This means they don't completely follow the path I've already described - cutting the odd corner here and there - but it looks cool and will be more useful in the long run.

Boom! Room outline done. The next step is to fill it all in.

In a previous incarnation of this approach, the interior was filled by creating segments linked to a central point. The problem with that is that you can't have concave shapes. I need something a little different. Also, although I said no grids earlier, I think a grid would be perfect for filling out the centre in a rough fashion. It might also make it easier later on if I need to do navigation and the like.

I found a formula for determining whether or not a point was inside a polygon and applied it to every point inside the room's bounding box. Check out this image:

The grey line is the rough outline - what happened to the circle after I perturbed the verts. That sounds nasty - perturbing verts. Shame really - it's going to crop up a lot.

The blue line is what happens after the smoothing with the final position being shown as a yellow outline.

The two red brackets show the extents of the room and the little vertical lines are the grid within it - grey ones are outside the polygon and yellow ones are inside.

The next step involves going around and removing any 'widowed' verts from the edges. Those are verts that, whilst being inside the polygon they don't have enough neighbours inside the polygon to form a quad. You can see an example of one sticking out at the very top of the image above. Once that's done, it's easy to go through and create the mesh for the central part of the floor - after a small amount of vertical perturbation, of course.

Rather than re-use each vert to create a single, smooth mesh, I've elected to duplicate the verts at each point so as to create a flat-shaded aesthetic. It will also enable me to mess around with individual UVs should the need arise.

|

| Looks a bit like a crepe I suppose |

Simply extend the skirt even more and raise up the outside edge. Then the Z-buffering can sort everything else out instead! It gives the floor a natural, cave-like look as well as rounding off the outside edge of the grid.

Doors

Obviously, the outside of the room is going to require some kind of wall. Then the wall is going to require some kind of doorway. That means I'm going to need some way of marking those outline verts as either solid (make a wall) or not (make a doorway). My doorway generator takes a direction and finds the closest vert. It then steps a random number of verts either side of that point and uses that as the centre of the door. Again, another random number determines how many segments the door takes up and therefore its width.

With the two end verts decided upon, all verts inbetween are smoothed out to form a nice, straight line. This will enable me to seamlessly match up a Corridor section.

A Door object is created that also consists of pillars. The plan was to use the pillars to cover up any gaps created by perturbing the wall verts of the room and whatever the room is connected to on the other side of the door. Note that 'door' in this sense doesn't neccessarily mean a physical door or obstruction - merely an aperture. I could certainly go back and block it up later when I figure out what I'm going to do about actual doors...

Corridors

Now to join two Rooms together with a Corridor. There's a function to link two Rooms together which generates a Door in each one, roughly in the direction pointing at the other one.

|

| Two Rooms linked by a Corridor |

I then create a path between the two doors. After messing around with a couple of different ways of doing it, I finally settled on the age old tradition of the Bezier curve. That involved looking up more code online as, although I know the name and have referenced it many times before in the past, I have no idea how they actually work.

Some judicious formula theft later and I have a nice, curvy line linking the two doorways together. From that it's easy to create two sets of outline verts - one for each wall - and make a ribbon that smoothly moves between each one. The obligatory perturbation of the exterior verts (ones that aren't joined to the doors at least) later and we've got ourselves a Corridor.

Layout

This was the tricky bit and involved more code that I am massively unfamiliar with. My basic plan was to follow the random-drop-and-dispersal technique for positioning Rooms. I'd generate a whole bunch of Rooms in a small space. Then I'd gradually move each one outwards until its footprint (plus a buffer) was no longer intersecting anyone else. Repeating the process for each one creates a pleasingly organic layout.

The next step is to link them all together in such a way that the Corridors don't overlap each other. This requires a couple of scary sounding techniques - Delaunay Triangulation and a Minimal Spanning Tree - both of which were pulled down from the internet after their suggestion by Tom, who loves a bit of procedural stuff.

The first one joins all of the Rooms together ensuring none of the links overlap each other. Basically you end up with a kind of mesh structure with the Rooms as the nodes or verts and the Corridors as the links between them. It's very clever and uses funny sounding words like 'circumcircle'. Leaving it like this would certainly create an organic and interesting looking dungeon but it doesn't create dead ends.

That's where the Minimal Spanning Tree comes in. It goes through the 'mesh' that you create with the Delaunay Triangulation and pares it down so that each node is still connected but only by the minimum amount of path necessary to encompass everything. The way it works in my head is like some kind of cross between A* navigation and a flood fill, but I could be wrong.

I may have to re-visit this part at some point and possibly poke more Corridors through to create loops for the player to get lost in. Otherwise the dungeon runs the risk of being too solve-able by simply wall hugging in a consistent direction.

Walls

|

| Delaunay + Minimal Spanning Tree + Corridor Walls |

Now to make everything look all 3D and stuff. I started in the Corridors as they were the simplest thing to implement. It was just a case of taking the exterior verts and extruding them upwards. Perturb them a bit then create a grid mesh like I did with the room floors and job done.

Actually, I changed the perturbation a little to tend towards bowing outwards from the centre line of the corridor. That'll make it easier on the camera later on.

Rooms were a little trickier in that there could be a variable number of individual wall segments, but the principle was the same.

Next up: Basic lighting, object placement and some kind of avatar.

(You may note that this is a bit of an odd project for me in that I still don't really have a plan for what the actual game part is going to play like, but I'm just enjoying building the world.)

Next up: Basic lighting, object placement and some kind of avatar.

(You may note that this is a bit of an odd project for me in that I still don't really have a plan for what the actual game part is going to play like, but I'm just enjoying building the world.)

Comments

Post a Comment